Pre-Settlement of the Red River Valley

An overview of the European exploration and early trade in the Red River Valley, prior to the 1870s.

The Red River Valley as it exists today emerged from receding glacier ice at the end last major ice age. Over a period of time that began about 14,000 years ago, an enormous "ice lobe" crept south from the Arctic, pulverizing all in its way and kneading the land into a new configuration. After reaching a point in what is today mid-Iowa, the ice sheet slowly receded northwards as the climate warmed, until about 12,000 years ago the land that is now the Valley was uncovered once again. The advance and retreat of the ice sheet had remade the land, smoothing it, in the words of geologist John Brophy, with deposits of "glacial and lake sediments so that the topography was now a broad, shallow basin" that gradually sloped away to the north. As melt-off and precipitation filled the low-lying ground a massive inland lake developed, covering some 370,000-430,000 square miles of ground, with depths of 200 to 700 feet. In the late 1800s, after the Swiss geologist Louis Agassiz, compiled evidence for the existence and impact of the ice ages, this massive lake was named Lake Agassiz. Lake Agassiz waxed and waned in size during climate changes over thousands of years, until the further retreat of ice permitted it to drain eastward and northward. Approximately 7500 years ago, the lake had disappeared, replaced by the Red River watershed that now extends from Lake Traverse (another product of the glacier age) on to the north.

The Red River is therefore a very young geographical feature. It is shallow, winding along a 550 mile course to Lake Winnipeg. The shallowness of the river, combined with its numerous bends and oxbows, plus the heavy annual snowfall that can readily occur in the prevailing climate, create ideal conditions for Spring flooding. Geological studies confirm that flooding was almost an annual event in the pre-settlement era. Several streams flow into the Red; but, as Brophy notes, the "stream network [has] great distance between streams, leaving vast areas untouched by any natural drainage areas." The land surrounding the river and streams is generally flat but also is filled with uneven depressions that can hold the runoff of the melting snow. Before the land was put heavily to the plow, these 'potholes' acted as "storage tanks" for ground water, and contributed nutrients to the soil. But the swamp-like ground aslo limited how much land could be planted; as late as the 1920s, the agriculture agent for Clay County Minnesota noted that farmers could increase their crops as much as thirty percent if drainage efforts were undertaken.

The Valley's climate has been one of extremes. Richard Pemble, professor of Biosciences at Minnesota State University Moorhead, noted in his study of Valley flora and fauna that, with temperatures ranging from lows of -40 to +110 degrees (F), and annual precipitation averaging from 16 to 25 inches pre year, the Valley's water cycle frequently follows a pattern of too-little followed by too-much. Because of the great changes in temperature and moisture, the plants and animals that thrived in the Valley were hardy species. Bison, fox, beaver, deer, muskrats, weasels and squirrels lived here in abundance. The river itself was filled with walleye, catfish, pike and drum fish.

This natural wealth in food sources drew Native Americans to the Valley.

The first people in the Red River Valley were ancestors of the American Indians. They were here after 10000 years ago. This estimate is based on findings at several archaeological sites with either radiocarbon dates, or diagnostic artifacts known from other parts of the continent to date to that time period, known to archaeologists as the Paleoindian. At Browns Valley Minnesota, near Lake Traverse, remains of an ancient man with these distinctive early artifacts was radiocarbon dated to 9050 years ago. This is one of the most famous of all Paleoindian sites in North America.

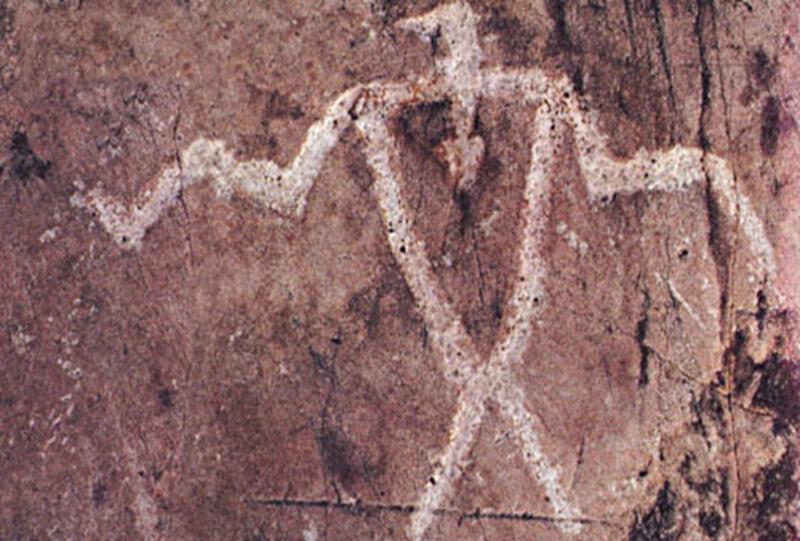

Carvings of birds and animals on rocks in various sites in what is today Minnesota and the Dakotas can be dated back thousands of years (the 'petroglyph' to the left is found in a state historic site just north of Mountain Lake Minnesota in the south central part of the state). Some of these carvings are estimated to be 5000 years old. But evidence of earlier human habitation exists in human and animal remains recovered by archaeologists and anthropologists. Buried kill sites of giant bison can be found in several sites around the Valley. The site of one kill is preserved at Itasca State Park, and is believed to be 8000 years old. Another such site was found near Kindred, ND. It dates to about 8000 years ago and lies in sediments along the Sheyenne River as it leaves the Sand Hills and flows into the Lake Agassiz basin. Extinct bison, stone tools, fire hearths, and the remains of a small shelter were found over an area suggestive of a very large camp; possibly indicating a group of 70-80 people.

In 1932, road builders at Pelican Rapids uncovered a fossilized skeleton of a young woman; this was later dubbed "Minnesota Woman" and was dated by researchers as being about 8000 years old. Other sites around the Upper Midwest contain evidence of copper mining and primitive smelting for tool and decorative use. These "early archaic" natives lived hard, precarious lives, followed animals on their seasonal migrations, and carefully learned to adapt themselves to the prevailing climates and environments -- so the remains tell us.

By the time of about 2000 years ago, a more complex culture Native American culture emerged call "Woodland" culture. The woodland natives resided for at least part of each year in the Valley region. They, like their predecessors, were hunters and gathers who could store some food surpluses in pottery made from clay and crushed rock. Minnesota State University Moorhead professor Michael Michlovic, noted in his paper on "Archaeology and Prehistory of the Red River Valley" that the decorative styles of pottery can tell us much about the "group identities and relationships in prehistoric times." By examining the pottery, Michlovic and others have been able to estimate the range of the Woodland culture in the valley and obtain solid information on the diet, migrations and interactions of the natives during that era. While many Woodland archaeological sites have been studied in the Valley, one notable locality is found near Glyndon, Minnesota. The site has a distinctive pottery style known as Blackduck. This is normally found in the lake-forest area of northern Minnesota and associated with moose, beaver, fish, bear and wild rice. In the Valley, however, about the only bone found was bison. The pottery was encrusted with burnt residues on the interior, which turned out to have indications that they were boiling maize (corn) in these vessels. Maize, a domesticated plant, was not previously associated with Blackduck or with any other northern Minnesota culture in prehistory.

A modest number of prehistoric cemeteries, or burial mounds are also found in the Valley. Based on early examinations of burial mounds discovered across the Upper Midwest, it is clear that these mounds belonged to a complex named the Arvilla culture. This also was part of the Woodland culture. (Excavation of such mounds is now prohibited by various statutes.)

Michlovic also noted that "the last of the culture-historical periods in the prehistory of the Red River Valley is known as the Plains Village" culture, which appeared in the region sometime around 800-900 years ago. These natives were almost certainly related to some extent to the earlier Woodland bands. The Valley natives continued to rely on hunting, especially of bison. They gathered foods growing in the wild but also cultivated maize and tobacco and probably amaranth and chenopodium as well, in garden plots.

Several sites of these village people are found on the western perimeter of the Valley along the Maple River south of Embden. Here are found small acre-sized communities with defensive ditches up to ten feet wide and five feet deep. These were settled farmers living on bluff tops above the nearby river using some of the same types of pottery found in the Minnesota Woodland, but other types found in the James Valley to the west. Clearly, these people had connections across the Woodland-Plains boundary. The sites date to about AD1450.

The Plains Village artifacts are very similar to those used by the Oneota, a skilled group pf farming natives who moved into the eastern plains regions about 1100 years ago. Oneota natives may have been the ancestors of several plains "tribes" that European explorers and traders came into contact with in the late 17th and early 18th century -- the Omaha, Winnebago, Oto and Iowa.

In all, there is abundant evidence that the lands of the Valley were continuously and sometimes, intensively, used before the coming of the Europeans. While the evidence strongly suggests that native life in the Valley was mostly seasonal rather that year-round, by the latter part of the prehistoric period relatively sedentary farming villages were in existence. It is clear from this evidence that natives could make a claim to the land, and that the Europeans would have to take those claims into account as their settlements drew ever closer to the Red River.

Furs first drew the Europeans to the Red River watershed. France had dominated the North American fur trade since the 1500s, operating out of its settlements at Quebec and Montreal and making use of the Great Lakes watershed in order to trade European goods for furs with the Native Americans that its traders (colorfully termed 'coureurs des bois' and later 'voyagers') could reach by small fleets of canoes. By the late 1600s, Great Britain determined to challenge France's interior fur hegemony. In 1668, two small British vessels, the Nonsuch (see replica at left) and the Eaglet, loaded with enough goods to make them what a Canadian historian termed "floating department stores," set forth from the port of Deptford, bound for Hudson's Bay. Funded in part by merchants in Boston (Massachusetts Bay Colony), the ships were to create a 'trading station' in the southern end of the Bay. The Eaglet developed leaks and was forced to abandon the expedition, but the Nonsuch continued on and made land in the south end of James Bay. The crew threw up a stockade from spruce trees, and proceeded to trade the stores wares to natives living near the bay. They remained at the bay for several months, often bored but generally free of the scurvy that often plagued crews of these long voyages; the shipwright cobbled together brew of "spruce, beer and lemon juice" for this purpose.

In June of 1669, after having amassed a fortune in furs and concluded a "League of Friendship" with a local chieftain, the men of the Nonsuch made preparations to go home. The League agreement gave them title to the stockade and the land around it (whether the chieftain understood that is unclear). The fort, now named Fort Rupert, gave them ongoing access to the the mouth of the adjacent river (likewise named Rupert River) and this led into the interior of what is today Manitoba. From this point British Fur traders would penetrate the north-central part of North America. In 1670, the British crown authorized the creation of the Hudson Bay Company for maintaining control of the trade in furs for this part of the continent.

The Hudson Bay Company became immutably linked to the subsequent settlement and history of Manitoba and the Red River Valley. Hudson Bay traders explored the rivers and lakes throughout this part of Canada and followed the watershed of the Red River of the North, seeking the most advantageous trade routes. The trade was enormously profitable for the Company, but hellishly hard for the men who served at the various trading posts: "very troublesome to write," recorded one of the post agents lived for long months along the Bay, "ink freezing on my pen." "Frozen feet and no wonder, as the thermometer for the last three nights was -36, -42 and -38," wrote another. "Rain froze as it fell -- if we have one hour fine weather, we have ten bad for it," wrote a third. As for those who ventured forth in canoes to explore the interior, hauling goods to trade for furs, it was often even worse. They paddled for hours through lazy steams, raging rapids and mosquito-infested sloughs, routinely carried 200-300 pound loads along narrow Indian trails and risked their lives when trying to communicate with yet another band of peoples whose language they could not understand. One accident could lead to broken limbs and death, one cold night to fever and death, one error in protocol to misunderstanding and brutal death. But the profits were great enough to persevere. Over time traders 'married' native women in ceremonies that created alliances with local natives, and produced children who could grow up to be act as go-betweens and translators.

Furs became the coin of financial and political empire. At one point Hudson's Bay controlled all of Britain's trade for over a third of the future nation of Canada and a large chunk of the future United States. France did not take this British success calmly: from the remainder of the 17th century until the middle of the 18th century, Britain and France fought a series of wars for imperial control of trade in several parts of the world, including the fur trade in North America. Britain won this extended conflict with the conclusion of the French and Indian War in 1756.

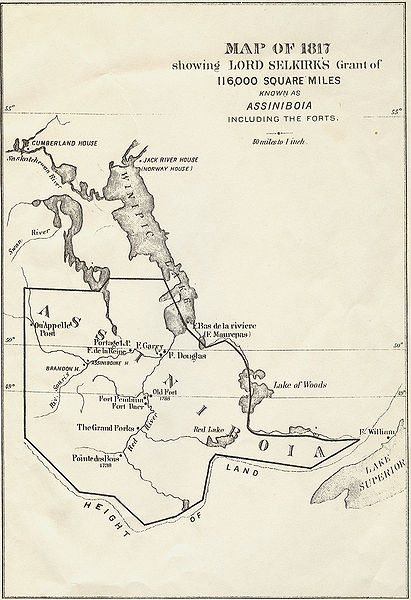

The first major agricultural settlement established by the British in the Manitoba region was the Selkirk Colony, in 1811. The colony was the brainchild of Thomas Douglas, 5th Earl of Selkirk, a Scottish laird. Lord Selkirk had for years been seeking a place to establish a North American colony for displaced Scot farmers who had lost their livings when ever more land in Scotland was enclosed for sheep. The British crown and parliament had encouraged this ongoing process for decades, as a method of building the empire's profitable woolen goods trade; they had succeeded so well that between 1760 and the early 1800s over 40,000 displaced Scots had left their homeland for overseas colonies. In 1803 Selkirk had helped to settle some 800 homeless highlanders on Prince Edward Island. A year later he paid out funds to help another group establish the hamlet of Baldoon in southern Ontario. But it was the lands of the Manitoba prairie that drew his most avid attention. In 1808, Selkirk visited Montreal and met with shareholders in the Northwest Fur Company, the only real rival to Hudson Bay for Canadian pelts. After extended talks with the already renowned explorer and entrepreneur Alexander Mackenzie, Selkirk approached the board of directors of Hudson's Bay, in which he held considerable stock, and persuaded them to let him fund a colony on a huge tract of land extending south of Lake Winnipeg, reaching east toward Lake Superior and south nearly to the banks of the Missouri River. It encompassed nearly 75 million acres in all.

(1)selkirk colony

The first contingent of colonists left for Hudson's Bay in July of 1811and arrived at the Hudson's Bay post of York two months later. It was too late in the season to push on south and start building, so the colonists spent the long winter at York. It was miserable experience, as the men, far from home, spent endless days in small shacks miles west of York, surviving on a diet of deer and ptarmigan meat and suffering terribly from scurvy. It was not until mid-1812 that they had recovered sufficiently to move south and begin the colony at the junction of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers. They began building their stockade and buildings on the west bank of the river junction. The colony leaders meanwhile laid out the plan for assigning strips of land to each farming family. While these leaders knew that it would take years before substantial crop harvests would be achieved, they also knew that Hudson's Bay Company would pay good prices for the grains that the colony grew. With time, they expected the colony to become a solid success.

But this plan did not reckon with Hudson Bay's great rival, for across the river from the developing colony there was a post manned by the Northwest Fur Company. The investors in the Northwest Company did not welcome the farmers. They viewed Selkirk's plans to turn these lands into farms as a direct threat to their own interests: food sold to Hudson Bay Company would benefit only the Northwest Company's competition; farms would not only reduce the populations of the beaver and muskrat but also drive the buffalo from the area, and buffalo was the source the Northwest Company used for supplying its canoe traders with pemmican, grease and tallow. The farmers also learned that their fur-trading neighbors wished them gone from the land, for group of mixed-blood employees of the Northwest Company rode in to tell that that an agricultural colony "would not be permitted" to interfere with the trade in furs.

This force at the disposal of the Norhwest Fur Company were the Meti. The descendants of French fur traders and Native Americans, the Meti were "middle men" of the fur trade. They had the skills to engage in all aspects of the trade, from trapping to negotiating. (2) Those Meti allied with the Northwest Fur Company resented the actions of the Hudson Bay investors in "giving their lands" to these farmers who threatened to reduce the fur population they relied on and could drive away the buffalo they relied on for both food supply and trade source. Skilled with horses and armed with muskets they obtained by Northwest agents, the Meti were a force that required careful handling. From 1812 to 1816, encouraged by some of the Northwest agents, Meti horsemen harassed the Selkirk colonists by raiding their farms in the dead of night, killing livestock and damaging crops. They also intercepted supplies sent to the colony from York.

Then, in June 1816, these harassment tactics changed to open warfare. Cuthbert Grant, a half-Cree warrior with large following among the Meti, met the colony's governor, Robert Semple and some with his advisers in a field called Seven Oaks south of the colony. The men argued about the continued problems between the two groups and as the words became heated someone -- no one has ever satisfactorily identified who or which side -- drew a weapon. The Meti then surrounded Semple's party and killed all but four of them. Disillusioned by the climate and the conditions, some of the inhabitants at the colony had already left by that time. Now more left in fear of another "Seven Oaks Massacre." Some of them went south toward a smaller trading post and town called Pembina.

No one knew for certain if Pembina was part of British territory or the United States. The 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the American Revolution had established the northwest boundary between the new nation and British Canada was to be established "...through the Lake of the Woods to the northwestern most point thereof, and from thence on a due west course to the river Mississippi." This quickly proved to be rather meaningless because no one could establish the origin of the Mississippi River for over fifty years. David Thompson a Canadian explorer who worked at one time or another for both the Hudson Bay and Northwest Fur companies, had surveyed much of the region and was inclined to believe that the Mississippi began well south of the 49th Parallel on the map -- about where Pembina stood. But American surveyors and statesman felt the river's origin was further north, and they held to this belief all the more after President Thomas Jefferson purchased the "Louisiana Country" from France. After Meriwether Lewis and William Clark completed their expedition to the Pacific, the American government were all the more anxious to have the national boundary resting as far north as possible.

Profit was as much a motive as national pride in this question. With Hudson's Bay blocked by ice for large parts of the year, the Manitoba region fur traders and farmers alike had engaged in trade with American merchants. One account in the fur trading records relates how in 1814, Lord Selkirk made arrangements for two Americans to deliver a herd of cows to the colony by way of the Des Moines and Red Rivers. In 1817, "King" Joe Rolette, a trader whose son would play an active role in the early history of Minnesota, corresponded with Selkirk concerning a proposed cattle sale. Selkirk was at the colony that year, having travelled there by way of eastern Canada. After leaving the settlement he went on south and made arrangements with a party of Dakota Indians for buffalo meat to send to the colony, then traveled on, down the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers on to St. Louis and ultimately home to Europe. The only grew only slowly and never really succeeded as an agricultural venture It eventually was dissolved, its last members joining other communities.

American traders who did business with those Europeans living up on the Manitoba plains invariably made their expeditions with combination of canoes, flatboats and two-wheeled carts, usually drawn by oxen. The oxcart trails became the 'international highways" between the two countries. The cart trade with settlements like Pembina and the Selkirk colony, became very profitable. Norman Kittson's cart business grew to the point that by the late 1840s he employed hundreds of men and women between St. Paul and Pembina, and operated over 600 carts. (3)

Americans who went into the fur trade amassed even greater profits. John Jacob Astor, a German immigrant in America, had made considerable money in the eastern fur trade well before he decided to challenge the British interests up along the Mississippi, Missouri and Red Rivers. In 1808 Astor formed the American Fur Company. He spent the next decade eliminating British fur interests within the American boundaries. Assiduously pressing the U.S. Army to establish posts in such places as Prairie du Chien and Rock Island, he took over trading posts that the British had operated in these regions. By the end of the War of 1812 Astor had forced the Northwest Company to sell to him all of its interests south of Pembina. His master stroke came in 1816 when, after intensive lobbying, he got Congress to pass the Foreign Intercourse Act, a law that made it illegal for a foreign subject from conducting trade with the United States. This forced several experienced traders, especially among the Meti, to apply for American citizenship and go to work for Astor. A year later, the U.S. Army sent an expedition to the junction of the Mississippi and Minnesota Rivers to survey a site for another fort. Slowly, Astor was driving his fur competitors northwards and taking over their business. He completed his empire-building when the United States concluded an agreement with Britain in 1818 that finally settled their international boundary in the region by placing it along "a line drawn from the most northwestern point of the Lake of the Woods" and then south to the "49th parallel of north latitude" and then west along the 49th parallel to the Rocky Mountains. This agreement placed Pembina and the Red River Valley southwards firmly in U.S. hands. Astor's success made him eventually the richest American of his time. (4).

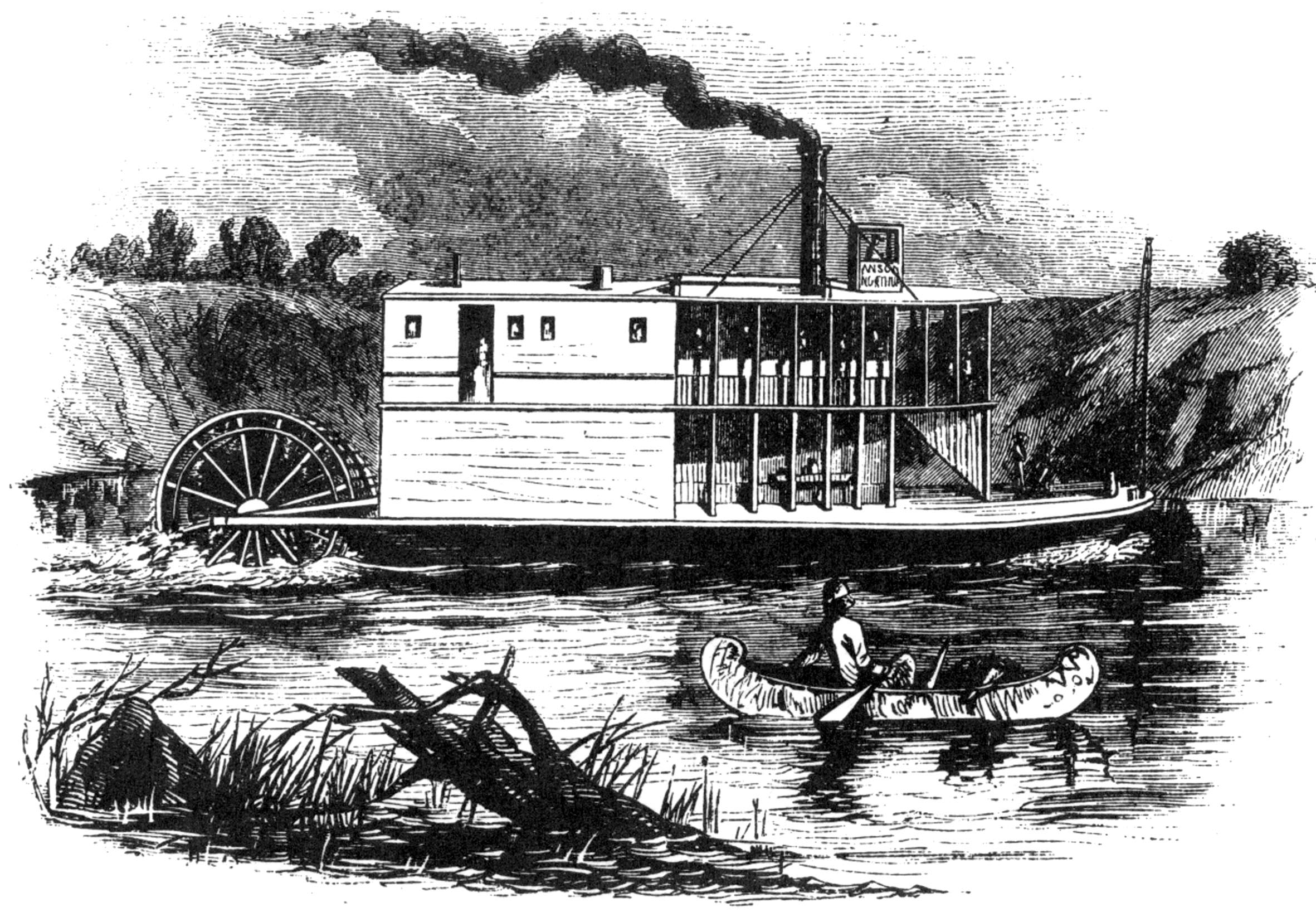

The cart trails blazed the way to settlement of the lands of the American part of the Red River Valley. Some of the primitive fur stations were rebuilt as way stations for the cart treks and, later, wagon trains that crossed the Red River on the route to the Montana-region mines. Burbank Station, near the present site of Moorhead Minnesota, was one such stopover. Built sometime in the 1850s, the station was used by the Burbank, Blakely and Merriam Stage and Freight Company to transship goods from merchants in St. Paul. The station closed in the early 1860s, but remains of it still existed when Moorhead was founded in 1871. The river steamer Anson Northup (left) began navigating the Red River in 1859 and other boats soon joined it. Were it not for the growing crisis over slavery and the Civil War, large scale settlement of the lower valley would probably have taken place in the 1860s. As it was, Michael Probstfield, a German immigrant and agent for Hudson's Bay, began farming on land near Georgetown in 1868. When the railroads reached the river in 1871, the pre-settlement era was over. Soon, the lands were forever changed: the prairie grass plowed under for corn, wheat and potatoes; the fur population reduced to but a shadow of its former preponderance; the swamp slowly drained; the Native American pathways and cart trails covered by steel rails and tarmac. For good and ill, civilization had come to stay.

- Selkirk likely had a long-term goal of taking control of Hudson's Bay altogether, but his immediate aim was another farming colony for displaced Scots. Mackenzie had investments in both Hudson's Bay and the Northwest Fur Company, but his main interest in encouraging Selkirk in the early stages of this venture was to expand Northwest fur profits at the expense of the Hudson Company. These conflicting goals helped shape the eventual clash between the 'trappers' and the 'dirt farmers.' See John M. Gray, Lord Selkirk of Red River (1963), and Peter C. Newman, Caesars of the Wilderness (1987).

- In the early 1800s, the Meti were seen as the offspring of French men and Native American women, while the offspring of English or Scottish traders and Native Americans were called "half-breeds." It was through their interaction with Northwest Fur agents that Meti came to have a greater sense of land ownership than most people with Native American ancestry and from this a strong sense of Meti identity became to emerge. For the full story, see Joseph Kinsey Howard's excellent book, Strange Empire (1952).

- The best work on the cart trade is Rhoda Gilman, Carolyn Gilman, and Deborah Stultz, The Red River Trails (1979).

- Astor's estate was estimated at 20 million dollars upon his death in 1848, the equivalent of about a half billion dollars in 2010.

Links to Other Websites Concerning Early Valley Geography & History